Daylight Savings Time Impacting Wildlife

This Sunday, March 9th, we are scheduled to fall back an hour in observance of daylight savings time. There has been much debate over previous years as to the purpose and benefits of this time change and whether it is still ideal. This shift in time was originally put in place in 1784 to cut back on light energy use and utilize more daylight. Today, this time adjustment may increase energy use like in the form of air conditioning and heat according to John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

While this time change may disturb our sleep cycles, it also alters our behaviors like driving, therefore impacting wildlife. The shift in schedules increases the chances of coming across nocturnal critters humans may not typically see. Many wildlife, especially those living in urban areas, can observe high human traffic areas to determine when they should be avoided at certain times of day.

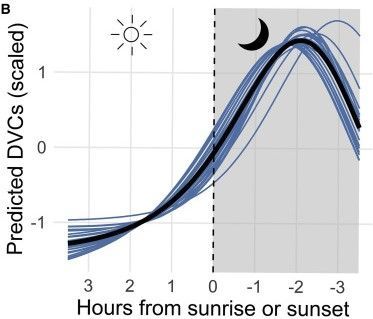

With our behaviors being changed biannually, wildlife must observe our behaviors and adjust their behaviors accordingly. However, there is a period of adjustment following this time change in which there is often an increase in human- wildlife conflict, particularly for motorists. With the shift of peak traffic times with deer-vehicle collisions being more common after sunset, there is a 16% spike in collisions correlating with the autumn time change in particular (Cunningham et al., 2022). Additionally, deer hunters know that the rut takes place during the daylight savings shift in the fall, creating the perfect storm of increased movement of deer with the shift in human movement.

As a solution to this large increase in deer collisions coinciding with peak commute times, Cunningham’s team suggested implementing permanent daylight savings. Finding that 10% of deer vehicle collisions occur during the time change in the fall, a more gradual approach is estimated to lower these statistics. The use of permanent daylight savings is estimated to decrease collisions with wildlife across the United States up to Alaska. This would still offer the optimization of time and energy resources while creating a less drastic change of time for both humans and wildlife. If this change was adopted, the research by Cunningham’s team estimates saving about $1.2 billion annually from reduced deer vehicle collisions. Additionally, this transition is estimated to reduce annual collisions by over 36,000, which can decrease the risk of human injury when colliding with these larger animals.

To avoid contributing to this statistic after this Sunday, consider the movement of wildlife when making any commute. Be extra alert and aware of your surroundings while driving on the road. It is best to stop and check for additional wildlife once one crosses the road, especially deer, which often cross in a line. To avoid potential accidents with oncoming motorists, it is recommended to slow down within your lane rather than veer off the path. If you hit a deer and it does not live, keep in mind the availability of salvage tags by the Michigan DNR to harvest the meat before it spoils.

Learn More

The Colorado Parks and Wildlife makes recommendations for motorists to stay alert, among other things, during time changes. Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention makes recommendations for personal health, including making gradual changes to our behaviors around the time changes. Overall, be mindful of your surroundings next week, especially when on the road. Improving deer habitat in certain areas may contribute to a decrease in large movements to help lower deer-vehicle collisions. Our On the Ground (OTG) program works with stewards across the state to improve habitat for many species, including deer. Visit our OTG website to learn more and take a look at upcoming projects.

Recent Posts