Glacial History of Michigan: How did we get our Great Lakes?

It is well known that Michigan was once covered in glaciers, or huge slow-moving masses of ice that formed from the accumulation and compaction of snow. But how exactly did this happen, and how did the glaciers create the Great Lakes we know today?

First, we need to take a trip back in time. The actual shaping of the state via the glaciers did not occur until late in the Pleistocene epoch (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago). These glaciers gathered in Canada and slowly moved over North America, burying its surface to a depth of 6,000 feet. The glaciers had four major centers of ice accumulation and one of them, called the Labradorian, occupied the area east of James Bay, Canada. This is the ice sheet that shaped the Great Lakes into what they are today.

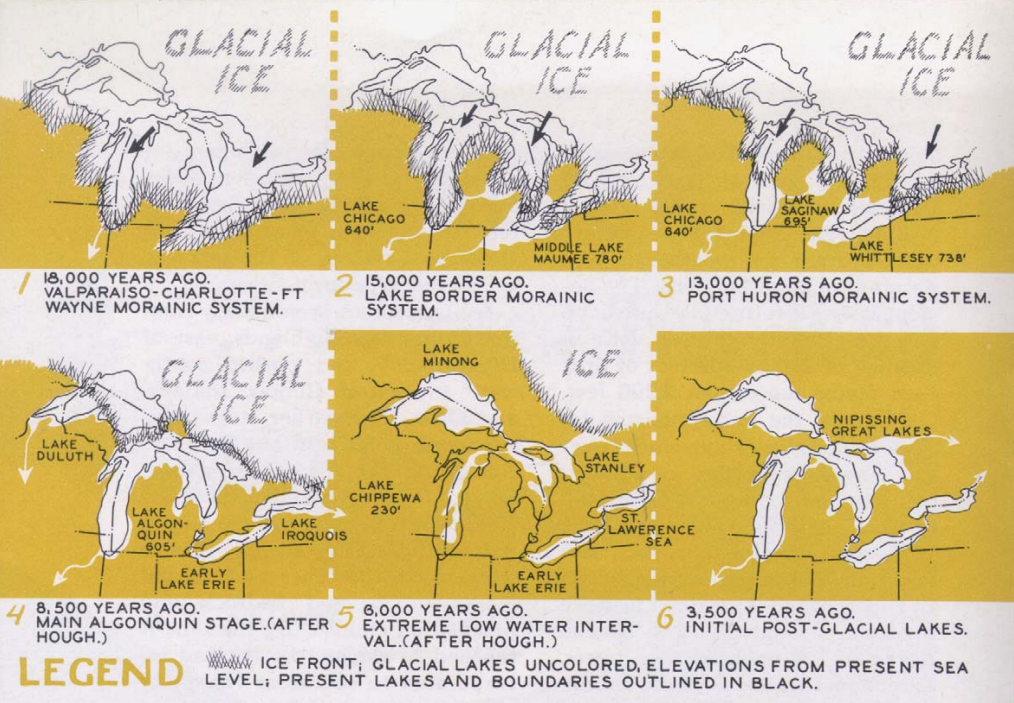

Currently, it is believed that there were several invasions of the ice sheets during the Pleistocene epoch. They would move downward from Canada into North America, then retreat back up to Canada and shrink into their accumulation sites. The last invasion is the one that created the Great Lakes. The Labradorian ice sheet retreated southward and worked itself into existing breaches and exposed bedrock, picking up and pushing rock material ahead of it as it went. As the ice sheet approached the Great Lakes area, it worked its way into old river valleys that were already present and divided itself into ice tongues, or major lobes of ice. As these ice tongues advanced, they deepened the valleys even further, turning them into river basins. When the ice sheet advanced back northward, the rock material it had deposited hardened into barriers. Water that had melted over time became trapped between the ice and these barriers and formed the earliest ancestors of our Great Lakes.

Around 20,000 years ago, a lower drainage outlet was uncovered near Rome, New York when the ice sheet had retreated from that area. This marked the first time that one of the early Great Lakes drained eastward toward the Atlantic, instead of south toward the Mississippi. After the ice had withdrawn completely from the lower peninsula of Michigan, the water level rose in the Michigan and Huron basins to form one large lake. Lake Erie had formed earlier when receding water in the Erie basin encountered resistant limestone in the Niagara River. This interaction created the great and powerful Niagara Falls.

The glacier then permanently retreated from the Great Lakes region and its weight caused the earth’s land mass to rise and “spring” upward, in a process called crustal rebound. This forced the St. Lawrence Sea to recede toward the Atlantic Ocean, and fresh waters helped form Lake Ontario and fill its basin, which took around 2,000 years. Crustal rebound again caused a drainage outlet near North Bay, Canada to close and drainage from the Great Lakes was now forced through Chicago and Port Huron. When the water levels dropped low enough, Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron were born.

The post Glacial History of Michigan: How did we get our Great Lakes? appeared first on Michigan United Conservation Clubs.

Recent Posts