Spring Awakening: Michigan Black Bears

Today is the first official day of spring, meaning warmer weather and sunny days are soon to come! In addition to welcoming spring, World Bear Day is occurring on March 23, 2025, to celebrate the important role the species plays in the ecosystem. However, there is only one confirmed bear species within the state of Michigan, the black bear (Ursus americanus).

History

Black bears in Michigan are estimated to have had a presence across the state since the glaciers retreated, according to the Michigan DNR. However, progressive settlement led to a loss of suitable habitat for many species, particularly in the southern portion of the state. The species was unprotected and treated as pests during this time, which pushed the species to the forests of the north. Regulations for bear management began in 1925, implementing a structure for hunters looking to harvest the species sustainably. By 2000, the bear drawing application began, where hunters could apply for a chance to win a license in the various bear management units across the range.

Current Status

Black bears can be found primarily in the western United States, Canada, and portions of Mexico. This species is not considered endangered or threatened, and their populations appear to be growing due to land management. A Michigan DNR report in 2022 estimated over 12,000 bears across the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan, demonstrating an increase since 2012.

Characteristics

Females of the species range between 90 and 300 pounds, while males can reach up to 500 pounds, according to the National Park Service (NPS). Before hibernation, individuals bulk up to gain enough fat to get through winter by eating foods high in fats, carbohydrates, and sugars. Females become sexually mature after 4 years, meaning they need to gain more fat than usual to feed their young before spring. Black bears have been recorded to live up to 30 years, according to NPS records, with most recorded deaths occurring due to hunting or vehicle collisions. The dens used during hibernation can range from crevices to burrows or old beaver houses, however, bears are not true hibernators and only drop their body a few degrees to slow down bodily functions and energy use until resources become plentiful again in the spring. The National Parks Service describes true hibernation as a reduction in metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature. Although they are a large predator, these bears are still capable of reaching over 33 miles per hour when running, making proximity dangerous. The coloration of black bears can vary from dark brown to cinnamon and blonde, as described by the National Park Service.

Conservation

Due to this species being one of the few predators in the state, human-wildlife conflicts can be uncommon but adrenaline-inducing. This reclusive species does not often interact with humans, however, interactions do happen in correlation with habitat loss associated with the growing human population. Although they are typically non-aggressive, black bears can attack when provoked or threatened. Due to their size and speed, it is best to remain a safe distance away from a black bear when possible.

Land management to provide the necessary habitat tailored to the species can help reduce the bear-human conflict. Due to their opportunistic nature, bears can turn to things like bird feeders and crops when their preferred foods, like native fruits and nuts, are limited or unavailable. Naturally, bears look for insects in addition to seasonal soft and hard mast to help regain weight after hibernation due to the high levels of fat, protein, sugar, and carbohydrates. As defined by the US Forest Service, mast is the term referring to nuts and fruits produced by plants; soft mast includes berries, and hard mast includes acorns. Additionally, their omnivorous preferences contribute to natural seed dispersal across their range, helping in the conservation of some native plant species. Bears prefer a landscape with a mixture of connected wetlands and uplands with clearings for a diversity of plants producing the necessary food.

According to the Michigan DNR, black bears can spend up to 7 months of the year in their dens, commonly in coniferous forests for the best heat retention. Biologists use the hibernation season to perform bear den checks, surveying the population to gather information on sex, age, and weight. By late March, bears are typically leaving their dens after winter hibernation to prepare for the next breeding season in May.

Hunting

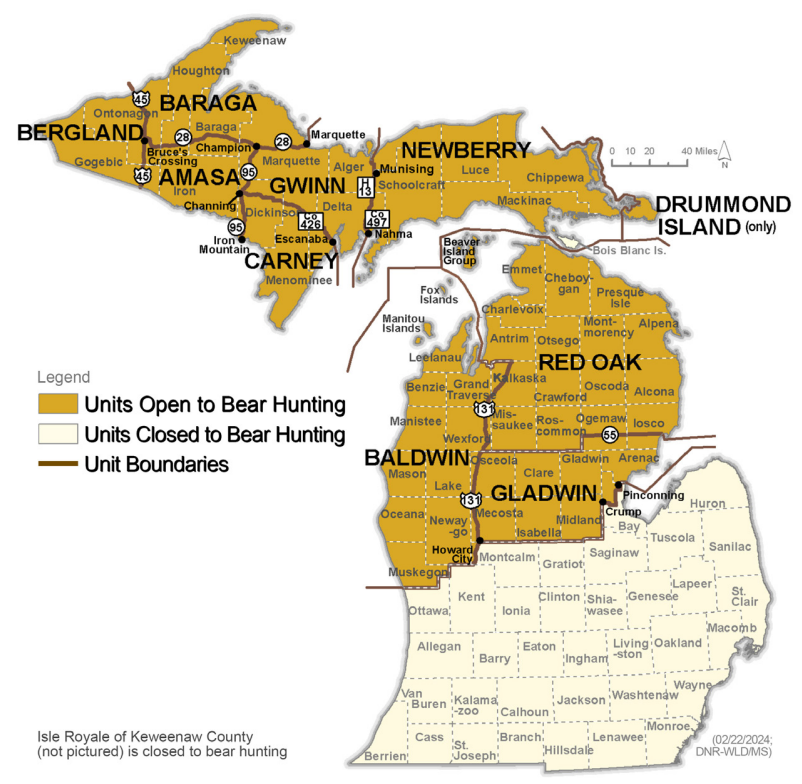

Bear hunting licenses are based on a drawing of $5 applications annually in which a single tag can harvest one bear that is not a cub (under 42 inches) or an individual accompanied by a cub. The application period for bear hunters to enter is between May 1 and June 1, with results available later in the month. The drawing system in Michigan is based on preference points, which are given at the time of application to be added to an individual's odds of winning the following year when not drawn. Drawing statistics can vary by license availability and number of applications per unit. After a successful hunt, a bear is brought to a registration station within 72 hours for reporting purposes. Non-residents of the state can also participate in the drawing and account for up to 5% of the allotted license quotas.

Learn More

To read about the bear hunting regulations in the state of Michigan, visit the DNR annual regulation handbook. This booklet contains helpful information to know before hunting bears for the season in question regarding legal hunting techniques, baiting, and diseases. More information about bear interactions can be found on what to do if a bear crosses your path. Organizations like Michigan United Conservation Clubs' (MUCC) On the Ground (OTG) program work to enhance and protect natural habitats for game species to improve the hunt for sportsmen and decrease negative human-wildlife interactions. MUCC holds a position on the Bear Forum, an annual stakeholder advisory group working with the DNR and other interested stakeholders to further bear management in the state. MUCC has fought since its inception for the right of hunters, trappers, and anglers to be the primary source of wildlife management in the state of Michigan.

Recent Posts