7 MYTHS OF MICHIGAN'S PUBLIC LANDS

by Paul Rose, from the Northern Michigan Conservation Network

Many may recall the debate in 2012 surrounding what was then known as the “Land Cap” bill. Although some improvements to the original bill were secured, PA 240 of 2012 became law and thereby established a 4.6 million acre limit on the amount of land that the State of Michigan could own and manage. One of the key provisions found in the final version of the bill was that the cap would be removed subsequent to the completion of an acceptable strategic plan for public land acquisition and disposal by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. The timeline for the planning process and its approval was to have been two years from the date of the law. Now, nearly three years later, there appears to be little support for revisiting the issue of Land Plan approval and land cap removal.

This is not to suggest that we need more net acreage of public land, or that all of these lands are in locations or configured ideally for effective management and use; instead, it is to that public land is not the “boogie man” as has been characterized by so many. In recent years, publicly-owned land has increasingly been blamed for nearly all of the economic and social ills which continue to face rural northern Michigan residents. As state and local governmental officials begin to accelerate the dissemination of a variety of myths pertaining to these lands, their words seems to attract new disciples who have helped to allow this misinformation to gain traction.

Although we would prefer to see a credible, third-party academic study prepared on the true cost-benefit of our public lands, it would seem unlikely that such research would change the minds of many who seem to be committed to this anti-public land hypothesis.

Alternatively, we have taken the opportunity to respond to a variety of myths which have emerged during the course of this public debate. The Seven Myths of Michigan Public Lands which follows has been prepared using the best relevant public information and economic data. Since most of the legislative initiatives pertaining to public land are limited to State of Michigan holdings (as opposed to Federal lands), these will serve as the primary basis for our discussions.

Myth #1 – Michigan has too much public land.

As we wrote last month, a recent USA Today survey ranked U.S. states for their perceived “well-being” as determined by their residents. Based upon the study results, six of the top ten states in the nation also ranked among the top twelve states in the percentage of public land area. The main exceptions to this trend were the three states which have been more economically insulated through natural resource production (Texas and South Dakota) and agricultural production (Nebraska).

Conversely, the lowest ten states in the ranking for resident “well-being” included four states in the lowest ten in public land ownership; seven of the lowest ten ranked being in the bottom one-third in terms of public land ownership.

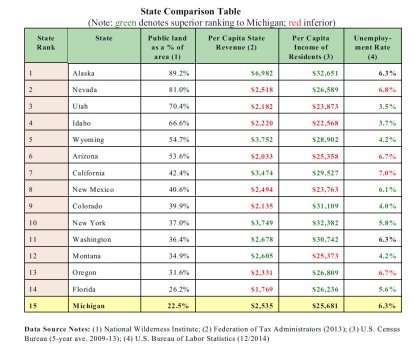

Research shows that of the fourteen States which have more public land than Michigan (as a percentage of total land area), nine have higher per capita personal incomes and ten have the same, or lower, unemployment rates. For those who may want to assume that this is a statistical anomaly attributable to rural western states, among those states with a greater percentage of public land than Michigan are Florida, New York and California.

The point is not that Michigan should aggressively acquire more public land, but rather the argument that Michigan’s economic challenges are somehow linked to Michigan’s public land inventory is simply not based on fact.

What is clear is that our state’s lack of economic diversity and what we do with the other 78% of our land area is far more relevant. Combine Michigan’s nearly $20 billion tourism economy, its $17 billion forestry economy with the fact that Michigan sells the third most hunting licenses and fifth most fishing licenses in the country, most reasonable people would agree that we are making very effective use of our public lands.

Myth #2 – The large amount of public land has limited economic development in northern Michigan.

Fact: there is no shortage of private land available for economic development in those areas which have a high percentage of public land. Most northern Michigan communities have previously developed community-sponsored business or industrial parks, most of which have realized only limited occupancy and, in some cases, have completely failed. On a percentage basis, many of these areas have more private land for sale than other areas of the state where little public land exists. Even if the myth about a private land supply shortage were to be true, the anticipated divestiture by owners of commercial forest lands (in the U.P.) and many of the hunting clubs in northeast Michigan will result in a new supply of forestry/recreational-use lands without having to force the sale of public holdings.

Unfortunately, many areas of rural northern Michigan are seen as being unattractive for business expansion or industrial development. This, for a litany of reasons, none of which are related to the amount of public land being found in these areas. Although most of us feel that it is a blessing to be surrounded by the Great Lakes, the fact remains that the shape of our state does not lend itself well to connection to central interstate highway and transportation systems – a condition which worsens the farther north one travels.

To suggest that the State of Michigan never sells or conveys public lands for the benefit of local communities and its residents is also untrue. There are many instances where agreements have been established to provide for a release of state lands when certain conditions established to protect the public interest have been satisfied. One such example was created near Grayling for a tract of land near I-75 and Four Mile Road.

The original Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) provided for the state’s release of a 1,700+ acre tract of land for industrial development. When the anticipated demand for the project never materialized, in 2007 the State agreed to consider an alterative proposal from Axiom Entertainment for a proposed theme park. Because the State’s sale contingencies were never credibly satisfied, combined with the declining economic conditions which existed at that time, we were spared what would have been, in all probability, a failed development. Had this land sale proceeded aggressively as was originally being sought by many project supporters, we may have found it necessary to use public resources to reclaim, recover and restore a significant portion of those 1,700+ acres.

Although this example should not preclude the consideration of future possible endeavors involving State-owned land, the point is that thorough due diligence must be applied together with a high level of process transparency and public engagement in advance of such transfers.

Myth #3 – Northern Michigan local units of government face funding shortfalls because of the large percentage of land which is publicly-owned.

Another widely accepted perception which has been advanced by many northern Michigan governmental officials over the years is the contention that their budgetary problems are caused by the limited tax base resulting from the large areas of public lands. Although the reimbursement paid to counties for state land through the Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) system is probably still not reflective of what we would contend to be its true value, this is only part of the problem.

Alternatively, why are we not debating the number of township governmental units we are trying to support with a centuries-old system which has its roots in the original settlement of the Northwest Territories? Originally selected on what was nearly an arbitrary basis, this 6 mile square township grid system was assumed to be necessary because of the belief that all lands would be settled and placed into active agricultural production. Instead, thousands of acres became failed homesteads and played-out timber lands which were eventually forfeited to the State of Michigan for non-payment of taxes.

Although some consolidation of this original township grid system did occur, in many instances what remains to this day is a mind-numbing number of local governmental units. Given our state’s efforts to reinvent itself, now would seem to be a good time to reexamine this system.

It is also worth recognizing that after consideration is given to the cost of delivery for the necessary public services, the net revenue gain to local governments resulting from the presence of a privately-owned rural residence is likely to be minimal when compared to the state’s PILT reimbursement system for lands which require no public services.

Again, we would agree that the methodology and appropriate level of county reimbursement for public lands should be reexamined and an amount established which recognizes its true value to the state’s economy and residents. This argument should not be advanced, however, through marginalization of the benefits of our public lands.

Myth #4 – What good is public land if you can’t use it? Too much public land has restricted access.

Perhaps none of the myths regarding State of Michigan owned/managed lands has been the subject of more misinformation than has been the issue of land use restrictions. While it is true that the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, the Natural Resources Commission and legislative actions have resulted in the designation of some 125,000 acres of natural or wilderness areas, nearly 50,000 of these acres is represented by the Porcupine Mountain Wilderness area.  When other special management areas such as the Pigeon River Country State Forest are added to this 125,000 acre amount, the resulting 230,000 acre total represents less than 5% of the state’s total inventory – hardly an amount which would be seen by most as being unreasonable. It is also worth noting that even these natural or wilderness areas are largely open to most forms of non-motorized recreational use.

When other special management areas such as the Pigeon River Country State Forest are added to this 125,000 acre amount, the resulting 230,000 acre total represents less than 5% of the state’s total inventory – hardly an amount which would be seen by most as being unreasonable. It is also worth noting that even these natural or wilderness areas are largely open to most forms of non-motorized recreational use.

Myth #5 – The State of Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund is contributing to the problem of public land with additional purchases.

During its nearly 40 year history, the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund has provided nearly one billion dollars in funding for both local and state recreational projects. These include both recreational facility and infrastructure development in addition to land acquisition. In spite of being nearly an annual target of a variety of legislative reform initiatives, it is worth noting that land acquisitions made through the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund (MNRTF) represent only 3.5% of the state land ownership total. Because of the greater flexibility for potential land uses, the MNRTF remains the best tool available to make further strategic public land acquisitions at both the state and local levels.

Myth #6 – The State of Michigan just keeps adding to the inventory and never gets rid of land.

As far as the issue of “surplus land” goes, the preceding decade saw the Michigan Department of Natural Resources go through a multi-phase “land consolidation” process. This effort sought to identify those lands which were most suitable for disposal through a process which involved both internal DNR staff review and public engagement. Based upon our personal observations from having attended several of those meetings, the greatest opposition to specific land disposal recommendations came from the general public. As one regular meeting attendee said, “it seems that every 40 acres of public land has its own personal advocate, many of whom have a decades-long personal connection to the land.”

As previously discussed, many communities have benefitted from the strategic transfer of public lands for community development or utilitarian needs. Those who may advocate for a large scale reduction in our public land inventory may wish to give consideration to the likely implications of such an initiative, specifically the negative effect this would have on the values of privately-owned lands throughout northern Michigan.

It is also worth noting that the Michigan Department of Natural Resources also pursues an active program of land exchanges which are typically initiated by a private landowner. These exchanges in most cases are a “win-win” for both the applicant as well as the general public through land ownership consolidation.

Myth #7 – When the state buys land it goes off the tax rolls and is also a bad public investment.

Unlike tax-reverted properties which represent some 52% of the state inventory, when land is acquired through a grant from the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund a PILT payment continues to be made at a rate which is similar to that which would have been paid at the ad valorem rate. Based upon the most recent Trust Fund Annual Report (January, 2014), the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) obligation for prior acquisitions represents $1,250,000, or nearly 10% of total annual Trust Fund project spending.

As a result of Public Acts 603 and 604, in 2013 PILT payments to Michigan counties for most other state-owned lands were increased from $2 per acre to $4 per acre. Although significantly less than what the revenue/tax obligation would be if held in most private ownerships, given the absence of necessary public services and the overall economic benefits of the land to the area, this amount is not unreasonable until a more sustainable reimbursement model is established.

When one considers that it is a renewable and perpetual economic resource, public land is an outstanding asset. If we were to conservatively assume that just 10% of our state’s $20 billion dollar annual state tourism economy is attributable to the presence of State Parks and Michigan’s public land, $435 per acre in total revenue would be suggested ($2,000,000,000/4,600,000 acres = $435/acre). If we were to assume a land ownership replacement cost of $3,500 per acre, an amount which considers riparian ownership, on a straight-line basis this would suggest an 8 year payback ($3,500/$435 = 8.0). Even at $4,000 per acre, the recovery period is only 9.2 years.

The significance of these figures is even more staggering when one considers that these lands also contribute to the State’s economy in other ways such as timber and mineral production, together with the all-too-seldom mentioned “quality of life.”